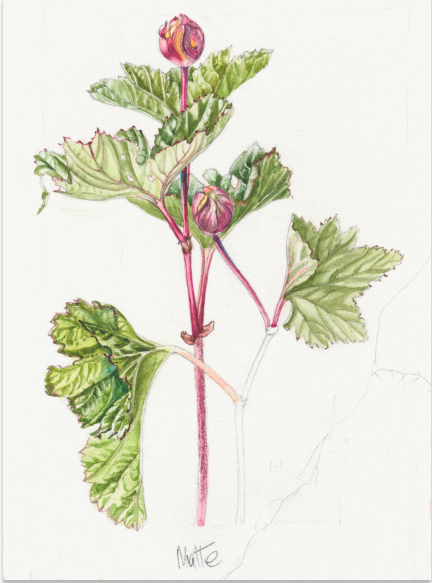

Rubus chamaemorus – Cloudberry -Multe

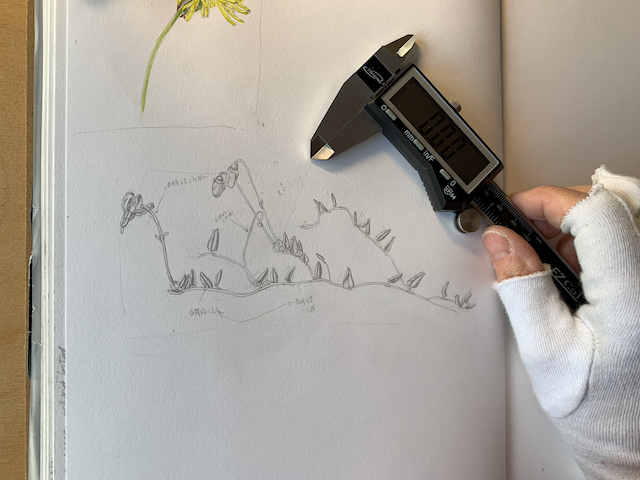

Planning the artwork.

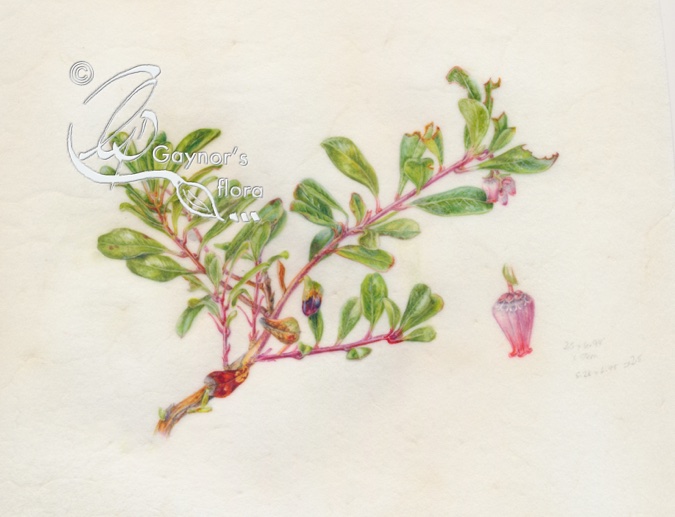

The piece of mounted vellum I had ready was 25 x 31 cm and I had seven mounted blocks all the same size. Finished, they needed to look like one series of pictures, but the Cloudberry was a plant so unlike the other ones. The element that linked was the habitat. As an example, I only found the Vaccinium microcarpum when following the rhizomes of the Cloudberry because the roots were completely intertwined.

Once I felt I had all the information I needed for each subject, I scanned the sections and manipulated them with editing software on my computer. I then compared them so that I knew each picture had similar information. The Cloudberry was the only one that was Dioecious. The series was about the fruit, so it was these that were prioritised, although I did include pictures of the flowers.

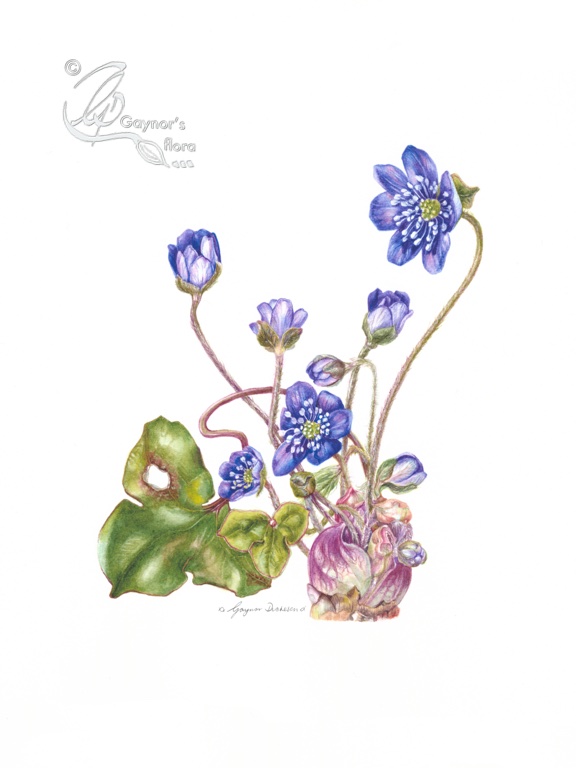

Because each cloudberry plant was either male or female and had male or female flowers, I needed to show the differences. The male flower is generally slightly larger than the female and the centre of the flower is completely different.

Both male and female flowers have the same number of sepals and petals, but the male flower has a ring of stamens round the base of the petals, with the very centre dipped and smooth. The female flower displays the gynoecium (female reproductive organs) with a ring of white, false stamens round the base of the petals.

From a distance and once you know what to look for, it is easy to tell the difference between a lot of male or female plants.

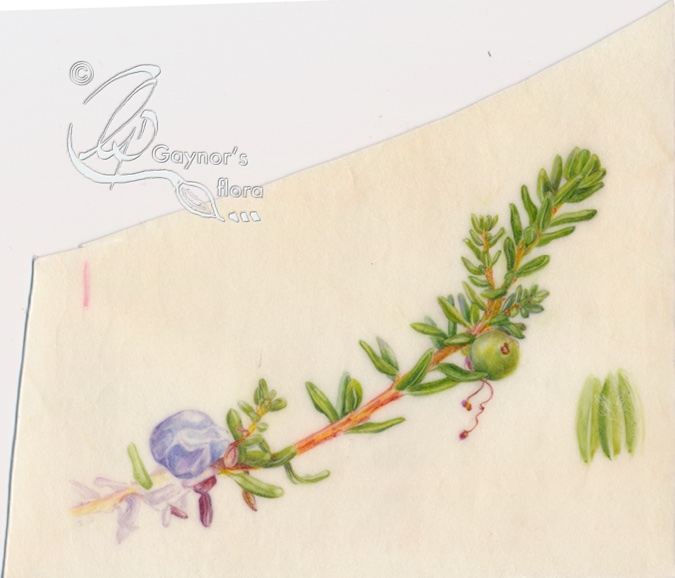

This sketch page shows more cloudberry sketches (with additional ones from the small cranberry). You will find both the deep red male plant and the sketches of the small cranberry in their respective final pieces of artwork.

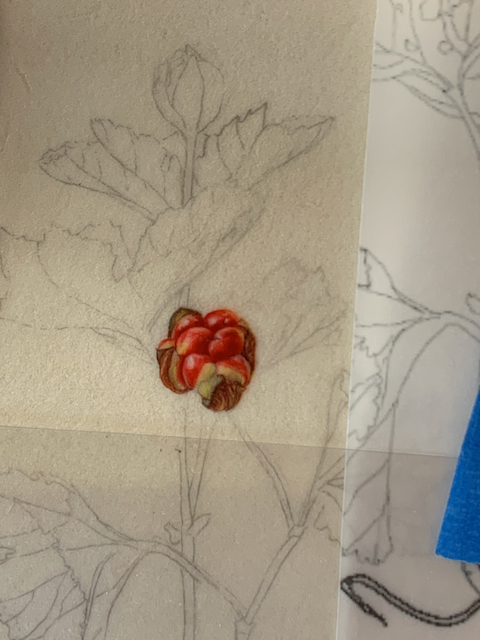

In 2018 when these sketches were done, the summer had been hot and tough for the plants. The Cloudberries ripened very early and by the time we arrived they were long gone. All that remained were some dry leaves and soggy berry remnants. But the sun had really worked well on leaves in the open, changing them from lush green to orange and fiery reds.

Once I had decided which elements were important for the picture, I did line drawings and moved them around digitally until I felt reasonably satisfied with the arrangement. Of course, in some instances adjustments were necessary and easily done on the computer. The line drawing composition above was almost the last one I made whilst well into the artwork.

In my final artwork I used several sketches as a basis. The sketches are used as a template whilst painting from an actual plant. Having the plant in front of me for the final artwork, enables me to paint its portrait as I see it, getting its botanical detail right at the same time as conveying texture and three-dimensionality. These are all things not easy to do from a photo.

I traced the whole composition to get the placing correct on my mounted vellum block, then each element was traced onto separate pieces of paper.

The vellum needed protection as I worked, and I used one of the old tracings that I had no use for, plus a clear acrylic sheet. All surfaces against the vellum are completely clean.

Once the image is traced over to the vellum I lifted off much of the loose graphite from the transfer process. I generally start with a pale wash, allowing this to dry completely, then remove the remaining graphite. I continue painting with a dry technique being sure to lay this very lightly.

Sketching was started in June 2014, the final artwork on vellum started July 2022 and finished in August 2022 except for the scalebars.

Cloudberries are a circumpolar boreal plant, occurring naturally throughout the Northern Hemisphere including the UK and Norway, although there is little fruit produced in the UK.

Source: Kew – Plants of the World online

Cloudberry cream recipe

This recipe for ‘Mountain Gold’ is served on very special occasions including Christmas. It is served with cakes/biscuits often made in the period leading up to Christmas. Many of the recipes include almonds .

500ml whipping cream

2 ss sugar

2 ts vanilla sugar (see recipe at end)

300ml Cloudberries

- Whip the cream together with the sugar until light and fluffy.

- Stir in Cloudberries and sprinkle with vanilla sugar to taste.

- Place in the fridge until serving.

Serving:

Extra Cloudberries, Shortcake Biscuits

(from https://www.detsoteliv.no)

Vanilla sugar (vanilje sukker)

2 Vanilla beans

300gm sugar

- Split the vanilla beans in half lengthwise and scrape out the seeds.

- Put the seeds into a blender with the sugar.

- Blend with the blades until the sugar has become completely fine-grained and well mixed.

- Put it into a glass with a lid and add to recipes as needed.

The next blog post about the Small cranberry will be on the 7th May 2023.